In my quest to ensure that I review every book that I read for Amazon (because I find other people’s reviews very useful) I’ve added my latest. It’s for the Kenneth Williams Diaries. I seemed to be reading them for ages – there are forty years worth of entries. It’s interesting for me because, during the time I was reading them I have also been maintaining this blog. While this isn’t quite a diary, the process is very similar and one paragraph in the diaries struck me as interesting:

The preoccupation with diary writing is caused by various things: the desire to keep a record which can be useful later, and committing to paper what can’t be communicated to a mentor … oh! all kinds of reasons, but fundamentally it is about loneliness.

Is it? Maybe it is. Who knows?

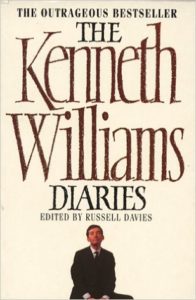

The Kenneth Williams Diaries, Edited by Russell Davies (Harper Collins, 1993)

I honestly think Kenneth Williams was unique. He certainly seemed to hate much about himself and didn’t have a great deal of time for a lot of other people. Sadly, the Diaries’ reputation precedes them and I expected more of the bitchiness that he is – supposedly – famed for. Despite that, there is plenty of Kenneth’s acid tongue in this book. His barbs are aimed squarely at his fans, his colleagues and the shows he felt obliged to work in. Some of the most intriguing insights are those that relate to the Carry On film series. Before Carry On made him famous, he was a well-respected stage actor. The Carry On films made him legendary (and wealthy) but he often felt they were beneath him.

I honestly think Kenneth Williams was unique. He certainly seemed to hate much about himself and didn’t have a great deal of time for a lot of other people. Sadly, the Diaries’ reputation precedes them and I expected more of the bitchiness that he is – supposedly – famed for. Despite that, there is plenty of Kenneth’s acid tongue in this book. His barbs are aimed squarely at his fans, his colleagues and the shows he felt obliged to work in. Some of the most intriguing insights are those that relate to the Carry On film series. Before Carry On made him famous, he was a well-respected stage actor. The Carry On films made him legendary (and wealthy) but he often felt they were beneath him.

Kenneth is well aware of his own nature. On 20 March 1987 he writes, “Everyone was v. nice to me … it is extraordinary that I’m so liked because I’m invariably rude & tetchy” and that sums up much of the book. You get a sense of love for the theatre, plays, and poetry and even for some of the work. However he is also offensive to many and seemed to have few good words for much of British Theatre. Much of the hate is due to an inner turmoil over the lack of companionship in his life (“Never to speak of my love for a man”) and some from the frustrations of his nature. Obsessed by noise and cleanliness the very act of living seems painful – and in the end his illness and genuine pain appear to get too much for him.

The diaries are very well written and Davies’ editing not intrusive. Williams certainly didn’t appear to edit himself and the result is a frank and articulate book. Words seem to flow easily which is, perhaps, not surprising for a man who made a living in the final years of his life from his large collection of humorous anecdotes. Spanning over forty years it’s hard to keep track of the players in Kenneth’s life and at 800 pages it’s not a light read. Nevertheless, the diaries are a vivid, malicious and (at times) very funny read into the world of a man who, in his day, was considered outrageous.