In my new-year nostalgia haze, I looked back at things I had written on this day (5th January) in years gone by. One post struck me more than the others. Fifteen years ago (2011), I answered a question posed by a Quora contributor: Will 2011 be the year that internet radio will pass traditional radio? By “internet radio”, I mean any kind of radio service listened to via the internet. I, like many others, said no. But I did find myself wondering whether I would answer it differently, all these years later.

The short answer is: no, I wouldn’t. We’re still a little way off the idea that internet radio truly passes traditional radio.

However, before looking at the radio numbers, I think it’s worth setting out a few things — if only so that we can come back in another fifteen years and see how the world has moved on.

According to the BPI, UK recorded music grew for an 11th consecutive year in 2025. For our purposes, streaming made up a record 89.3% of music consumption last year. I mention this simply to underline that streaming is now a real force in our lives, and that the streaming music services are major drivers of audio listening.

Audio consumption is still huge in the UK. Ofcom says that 93% of adults listen to some form of audio content each week, and that there has been growth across all audio streaming. Among younger people, this streaming trend is even more pronounced: 58%, up from 40% in 2019.

So, had the question been framed differently in 2011, I suspect we’d now be saying that most music is consumed via the internet. But music isn’t radio. And in spite of the efforts of Spotify’s AI DJ, and all those blokes with podcasts, the UK is still listening to things we would recognise as radio in 2011.

RAJAR’s autumn 2025 MIDAS survey tells us that around 39% of people listen to on-demand music each week, 24% to podcasts, 21% to music they own, and 10% to audiobooks. Live radio, meanwhile, still reaches a whopping 86% of the UK population every week.

RAJAR also tells us that AM/FM radio now accounts for under 30% of total radio consumption. So we’ve come a long way since 2011, when listening via a digital radio platform accounted for just over a quarter of all listener hours in Q1, with AM/FM making up the remaining 75%.

According to RAJAR, the most-used platform for radio is DAB, accounting for 42% of listening hours. Listening via smart speakers has been rising steadily and now represents 18% of live radio listening, while all online listening — including smart speakers, websites, and apps, and therefore what I am classing as “internet radio” — now makes up 28% of total listening.

So, fifteen years on, in the UK, internet radio’s share of all radio listening still sits below 30%. It is now more or less level with AM/FM, but DAB listening — which remains a remarkably convenient box with a simple, immediate, on-off button and no app to navigate — is the clear majority.

We still have some way to go before it becomes the year of truly connected radio, but the direction of travel is obvious. Come back in fifteen years for an update.

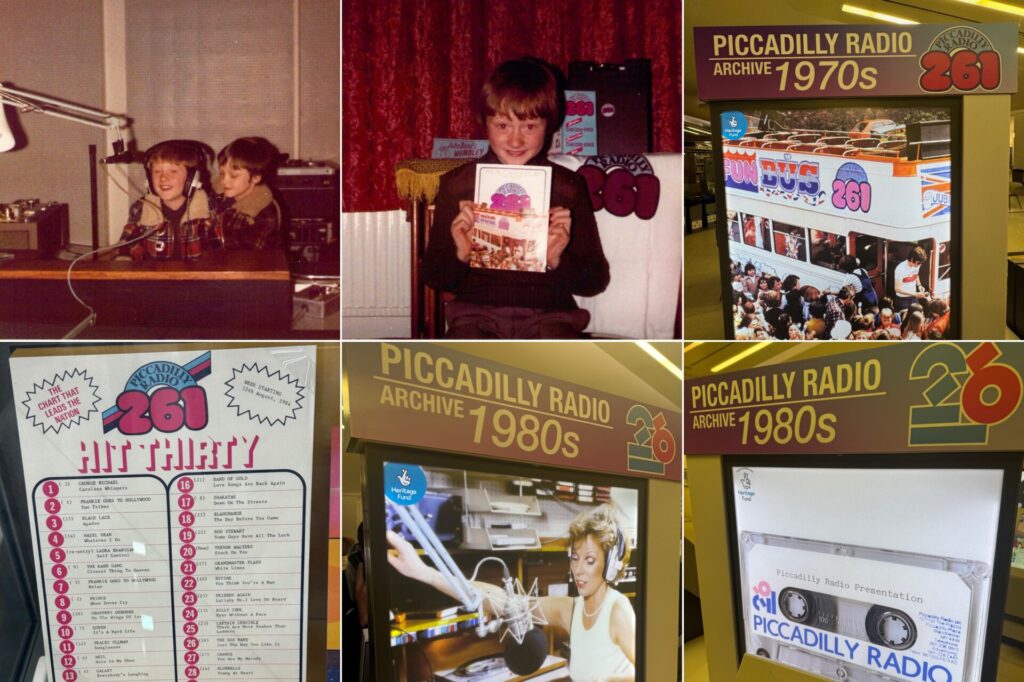

I’ve written a few times about my childhood love of radio. In the early 1980s,

I’ve written a few times about my childhood love of radio. In the early 1980s,

Chris Country

Chris Country